FOURTH SUNDAY OF LENT HOMILY YEAR C

Jos 5:9, 10-12 2 Cor 5:17-21 Lk 15:1-3, 11-32

The Fourth Sunday of Lent, often referred to as Laetare Sunday, serves as a moment of joyful anticipation within the penitential season, signaling the approaching celebration of Easter. The liturgical readings for this day, particularly in Year C, center around profound themes of reconciliation, forgiveness, and the transformative power of God’s mercy.

The First Reading, from the Book of Joshua (5:9-12), recounts the Israelites’ arrival in the Promised Land after their long journey through the desert. Here, they celebrate the Passover and partake of the produce of the land, marking the end of manna. This moment signifies not just a physical entry into a new land but a profound transition from their past hardships to a renewed relationship with God, free from the ‘reproach of Egypt.’

In the Second Reading, from 2 Corinthians (5:17-21), Paul emphasizes the concept of becoming a ‘new creation’ in Christ. He highlights that through Christ’s reconciling work, believers are entrusted with the ‘ministry of reconciliation.’ This passage underscores the transformative power of God’s forgiveness, urging us to embody and extend this reconciliation in our own lives.

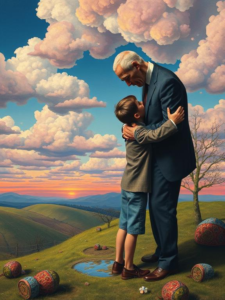

The Gospel reading from Luke (15:1-3, 11-32) presents the Parable of the Prodigal Son, a narrative that epitomizes divine mercy and forgiveness. It tells of a father’s unconditional love and readiness to forgive his repentant son, illustrating the boundless compassion God offers to all who seek reconciliation.

Collectively, these readings invite us to reflect deeply on our personal journeys of faith. They challenge us to recognize areas in our lives where we may be estranged from God or others and encourage us to embrace the grace of forgiveness. As we meditate on these scriptures, we are called to open our hearts to God’s transformative mercy, allowing it to renew us and guide us toward a more profound communion with Him and our community.

In today’s homily, we will delve into these themes, exploring how the scriptures beckon us toward a sincere conversion of heart and a renewed commitment to living out the reconciling love that God so generously extends to us.

Mass Readings For Fourth Sunday of Lent Homily Year C

1st Reading – Josiah 5:9A, 10-12

9 The LORD said to Joshua, “Today I have removed the reproach of Egypt from you.”

10 While the Israelites were encamped at Gilgal on the plains of Jericho,

they celebrated the Passover on the evening of the fourteenth of the month.

11 On the day after the Passover, they ate of the produce of the land in the form of unleavened cakes and parched grain. On that same day

12 after the Passover, on which they ate of the produce of the land, the manna ceased. No longer was there manna for the Israelites, who that year ate of the yield of the land of Canaan.

Responsorial Psalm – Psalms 34:2-3, 4-5, 6-7.

R. (9a) Taste and see the goodness of the Lord.

2 I will bless the LORD at all times;

his praise shall be ever in my mouth.

3 Let my soul glory in the LORD;

the lowly will hear me and be glad.

R. Taste and see the goodness of the Lord.

4 Glorify the LORD with me,

let us together extol his name.

5 I sought the LORD, and he answered me

and delivered me from all my fears.

R. Taste and see the goodness of the Lord.

6 Look to him that you may be radiant with joy,

and your faces may not blush with shame.

7 When the poor one called out, the LORD heard,

and from all his distress he saved him.

R. Taste and see the goodness of the Lord.

2nd Reading – 2 Corinthians 5:17-21

17 Brothers and sisters: Whoever is in Christ is a new creation: the old things have passed away; behold, new things have come.

18 And all this is from God, who has reconciled us to himself through Christ

and given us the ministry of reconciliation,

19 namely, God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ, not counting their trespasses against them and entrusting to us the message of reconciliation.

20 So we are ambassadors for Christ, as if God were appealing through us.

We implore you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God.

21 For our sake he made him be sin who did not know sin, so that we might become the righteousness of God in him.

Verse Before The Gospel – Luke 15:18

18 I will get up and go to my Father and shall say to him:

Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you.

Gospel – Luke 15:1-3, 11-32

1 Tax collectors and sinners were all drawing near to listen to Jesus,

2 but the Pharisees and scribes began to complain, saying, “This man welcomes sinners and eats with them.”

3 So to them, Jesus addressed this parable:

11 “A man had two sons,

12 and the younger son said to his father, ‘Father give me the share of your estate that should come to me.’ So the father divided the property between them.

13 After a few days, the younger son collected all his belongings and set off to a distant country where he squandered his inheritance on a life of dissipation.

14 When he had freely spent everything, a severe famine struck that country, and he found himself in dire need.

15 So he hired himself out to one of the local citizens who sent him to his farm to tend the swine.

16 And he longed to eat his fill of the pods on which the swine fed, but nobody gave him any.

17 Coming to his senses he thought, ‘How many of my father’s hired workers

have more than enough food to eat, but here am I, dying from hunger.

18 I shall get up and go to my father and I shall say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you.

19 I no longer deserve to be called your son; treat me as you would treat one of your hired workers.”’

20 So he got up and went back to his father. While he was still a long way off, his father caught sight of him and was filled with compassion. He ran to his son, embraced him and kissed him.

21 His son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you; I no longer deserve to be called your son.’

22 But his father ordered his servants, ‘Quickly bring the finest robe and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet.

23 Take the fattened calf and slaughter it. Then let us celebrate with a feast,

24 because this son of mine was dead and has come to life again; he was lost, and has been found.’ Then the celebration began.

25 Now the older son had been out in the field and, on his way back, as he neared the house, he heard the sound of music and dancing.

26 He called one of the servants and asked what this might mean.

27 The servant said to him, ‘Your brother has returned and your father has slaughtered the fattened calf because he has him back safe and sound.’

28 He became angry, and when he refused to enter the house, his father came out and pleaded with him.

29 He said to his father in reply, ‘Look, all these years I served you and not once did I disobey your orders; yet you never gave me even a young goat to feast on with my friends.

30 But when your son returns who swallowed up your property with prostitutes, for him, you slaughter the fattened calf.’

31 He said to him, ‘My son, you are here with me always; everything I have is yours.

32 But now we must celebrate and rejoice, because your brother was dead and has come to life again; he was lost and has been found.’”

________________________________________________________________________________

Moral Story: The Two Brothers and the Forgiving Father – Fourth Sunday of Lent Homily Year C

Once in a small village, two brothers, Daniel and Samuel, grew up together but took very different paths. Daniel became a devout man, following every religious rule meticulously, while Samuel fell into a life of mistakes and regrets.

One day, Samuel returned home, weary and broken. Their father ran to embrace him, overjoyed that his lost son had returned. But Daniel stood aside, angered that his brother, who had wasted his life, was being welcomed so easily. “I have been faithful all my life, yet you celebrate him?” Daniel complained.

Their father replied, “My son, you have always been with me, and all I have is yours. But your brother was lost and is now found; he was dead and is alive again. Should we not rejoice?”

That day, Daniel realized that true righteousness is not found in self-pride but in embracing God’s mercy and forgiveness.

10 Bible Verses on Reconciliation, Forgiveness, and God’s Mercy – Fourth Sunday of Lent Homily Year C

-

Luke 6:37 – “Do not judge, and you will not be judged. Do not condemn, and you will not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven.”

-

Matthew 6:14 – “For if you forgive other people when they sin against you, your heavenly Father will also forgive you.”

-

Ephesians 4:32 – “Be kind and compassionate to one another, forgiving each other, just as in Christ God forgave you.”

-

2 Corinthians 5:18 – “All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation.”

-

Romans 12:18 – “If it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone.”

-

Micah 7:18 – “Who is a God like you, who pardons sin and forgives the transgression of the remnant of his inheritance?”

-

Psalm 103:12 – “As far as the east is from the west, so far has he removed our transgressions from us.”

-

Colossians 3:13 – “Bear with each other and forgive one another if any of you has a grievance against someone. Forgive as the Lord forgave you.”

-

James 2:13 – “Because judgment without mercy will be shown to anyone who has not been merciful. Mercy triumphs over judgment.”

-

Isaiah 1:18 – “Come now, let us settle the matter,” says the Lord. “Though your sins are like scarlet, they shall be as white as snow.”

10 Religious Jokes on Reconciliation, Forgiveness, and God’s Mercy – Fourth Sunday of Lent Homily Year C

-

Pastor’s Wisdom:

Parishioner: “Pastor, I can’t forgive my enemy.”

Pastor: “Then let me pray for you.”

Parishioner: “Thanks!”

Pastor: “Lord, please give him a short memory!” -

A Child’s View of Forgiveness:

Sunday school teacher: “What must we do before God forgives our sins?”

Johnny: “First, we have to sin!” -

Saint Peter at the Gates:

A man arrives at Heaven’s gate. Saint Peter asks, “Why should I let you in?”

“Because I never sinned!” the man boasts.

Peter replies, “Then why do you need to be here?” -

The Self-Righteous Prayer:

A Pharisee prays, “Thank you, Lord, that I am not like other sinners.”

God replies: “You’re right. They’re humble; you’re not!” -

Confession Confusion:

A priest tells a boy, “To receive forgiveness, you must truly repent.”

The boy replies, “I do! But can I keep the fun memories?” -

A Patient God:

A man prays, “Lord, I’ve messed up again!”

God replies, “I know, and I still love you. But let’s try again tomorrow!” -

Mercy Over Punishment:

A Sunday school teacher asks, “Why should we forgive others?”

Little girl: “So they won’t take revenge on us!” -

A Long Prayer for Forgiveness:

A pastor prays for a long time. His wife whispers, “Are you repenting?”

“No,” he replies, “I’m listing everything to make sure I don’t forget!” -

Heaven’s VIP List:

A man asks God, “Who gets into Heaven first?”

God replies, “Those who forgive before they run out of time!” -

The Kindest Judge:

A man arrives in Heaven and says, “Lord, I was kind to everyone!”

God smiles, “That’s why you’ll enjoy my kindness now!”

10 Quotes from Great People on Forgiveness and God’s Mercy – Fourth Sunday of Lent Homily Year C

-

“To be a Christian means to forgive the inexcusable because God has forgiven the inexcusable in you.” — C.S. Lewis

-

“Forgiveness is not an occasional act; it is a constant attitude.” — Martin Luther King Jr.

-

“You will never forgive if you are waiting for perfect justice.” — Timothy Keller

-

“The practice of forgiveness is our most important contribution to the healing of the world.” — Marianne Williamson

-

“God’s mercy is fresh and new every morning.” — Joyce Meyer

-

“If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us.” — 1 John 1:9 (Apostle John)

-

“The weak can never forgive. Forgiveness is the attribute of the strong.” — Mahatma Gandhi

-

“He who cannot forgive breaks the bridge over which he himself must pass.” — George Herbert

-

“Mercy is greater than justice.” — Abraham Lincoln

-

“Let us always meet each other with a smile, for the smile is the beginning of love.” — Mother Teresa

________________________________________________________________________________

Homily For Fourth Sunday of Lent Homily Year C

Reconciliation

Against Self-Righteousness; Throw Yourself on God: Forgiveness; God’s mercy.

When history of our times is written, it will say that our popular art form is the motion picture film. Yet an aid to rapid – almost magical – learning has made its appearance. Indications are that, if it catches on, all the electronic gadget will be just so much junk. The new device is known as Built-in Orderly Organized Knowledge. It has no wires, no electric circuitry to break down. Anyone can use it, even children. It fits comfortably in the hands or promptly go forward or reverse itself, requires no batteries, and will provide full information on an entire civilization. The makers generally call this Built-in Orderly Organized Knowledge device by its initials, BOOK. The book in turn presents one of the most popular art forms of all time – the short story.

Among the most popular short stories of all time is the one in today’s Gospel. Because it comes after the stories if the lost sheep and the lost coin, it gives the facetious name to this section of St Luke’s Gospel as “The Lost and Found Department”. It is usually mis-called the story of “The prodigal Son”. It might better be called the story of “The Loving Father”. He is the main character and real hero. He is also the same Father who listens to us as we pray. The story is realistic and reflects keen psychological insight.

The younger of two sons going to his father and asking for his inheritance was within his rights under the Law (Dt 21:15-17). But the son’s coming to him like this was tantamount to saying that he wished his father dead. Nevertheless, under the law the father could choose to give his sons his property either while he was living or when he died. In either case, the division of the property would be the same. In a case like the present one, the elder son would get two-thirds and the younger son one-third.

In our story the younger son – because of immaturity, or selfishness, or irresponsibility, or a spirit of adventure, or whatever motivated the youth – chose to go his own way independent of his father. Opting for the pleasure of self-satisfaction, he came to one of the consequences of sin – isolation from community. When he was reduced to the degradation of taking care of pigs, the lowest of the low for a Jew, like an alcoholic who has hit rock-bottom he finally came to see himself as he really was. The young man resolved to return to his father’s house.

All the long way home he rehearsed a manipulative speech that he hoped would persuade his father to take him back – not as a son any more, but a hired hand. It is a tacky speech that plays on what he himself undoubtedly doesn’t put much stock in – his father’s reverence for God: “Father, I have sinned against God and against you.” If his behavior were from someone we knew today, it would elicit our contempt. The average human father might welcome him back, but with a stiff contract: Tow the line or else! He would love him, yes. But such a son would have to prove himself before the father could really forgive or forget.

What did this father do? Even as his son was far off, he saw him; he must have been waiting and watching all that time. He threw open his arms in welcome, and never let his son finish his rehearsed speech. The scene is well depicted in Rembrandt’s painting, Return of the Prodigal Son.The father is embracing the young son, his left hand the large strong hand of a man, his thumb giving obvious pressure through the threadbare garment on the boy’s shoulder. His embracing right hand, though, is the delicate hand of a woman, showing mercy and kindness.

The father’s forgiveness was total. He ordered his workers to put on his son the finest robe as a sign of honour, a ring as a sign of authority, and shores as a sign that he continued to be a son. His son wasn’t to be reduced to the status of slaves. In that culture, it was they who had no shoes. (Because slaves had no shoes even to recent times, poor African-American slaves sang the spiritual, “All God’s Chillun Got Shoes.” For them this meant heaven, when at last all people, even defenceless slaves, would receive their true dignity as persons.)

Again translated into modern terms, the father’s behavior would receive comments something like, “The old fool! No wonder his son is such a spoiled brat! The old man will be dead of a heart attack in a year!” But if we were put in the place of having to deal with our own best beloved, it might be a different story.

During the father’s celebration of his son’s return, the elder son makes his entrance for the climax of the story. He is smug in having done his duty to the father all the time his brother was away. His judgements, coming from a mentality of law rather than grace, of a hireling rather than a loving son, are rash, his speech mean. Just as the father had graciously cut off the humiliating speech of his younger son to show forgiveness, the elder brother cuts off the loving speech of his father to object. He refers to his younger brother as “your son” (v. 30), and the father gently rebukes him by referring to “your brother” (V. 32).

Perhaps we should give thought to the ways – many of them self-righteous – in which we can offend. In early – nineteenth-century Vienna, a famous preacher delivered a fiery sermon to huge congregation. He spoke of “that tiny pierce of flesh, the most dangerous appurtenance of anyone’s body”. Gentlemen blanched and ladies blushed as he elaborated on all the horrendous consequences of its misuse. Finally, he leaned over the pulpit to scream at his listeners; “Shall I name you that tiny pierce of flesh?” There was paralyzed silence. Ladies extracted smelling salts from their handbags. He leaned out father, and his voice rose to a hoarse shout. “Shall I show you that tiny pierce of flesh?” Horrified silence. Not a whisper or a rustle of a prayer book could be heard. The preacher’s voice dropped, and a sly smile slid over his face. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he concluded, “Behold the source of our sins!” and he stuck out his tongue. That’s a major way in which both the elder brother of Jesus’ story and we offend.

Paul’s words to the Corinthians jump out at us to let us know that we aren’t God’s slaves or hired help, but His children. Humankind hasn’t been the same since Jesus. All people have been invited to be God’s children. This means we are not creatures like the pew you’re sitting on, or the clothes you’re wearing, or your pet dog at home, but a creation – a new creation, like of which no mere human could have come up with – “brand new”, as a child might say. And because our heavenly Father is not self-righteous but the best possible, we are offered reconciliation with him. And reconciliation is the essence if the Church’s ministry.

Those of us who have ben profligate children can take consolation not only in the Gospel story, but also in today’s reading from the Book of Joshua. This book tells not scientific history in the current sense of the word, but the salvation history of God’s people. The Jews on the way to the Promised Land had undergone great battles with opposing tribes, as well as other hardships, which lasted a long time. Moses had led the people out of Egypt; Joshua would lead them into the Promised Land. The Israelites had crossed the Jordan and were about to become engaged in the conquest of Jericho. Because they preserved, they made it.

Today’s passage from the Book of Joshua reminds us that, no matter what our difficulties, we can make it, too. The only thing we need is persistence. Nothing in the world can take its place – not talent, nor genius, nor education. No matter what our difficulties, if we are determined enough to come to our heavenly Father during the remainder of this Lent, we can rejoice at the coming of Easter.

What lessons are in this for us? The first word of today’s liturgy speak of joy, the First reading and the Gospel of homecoming, and the Second Reading of newness. These are good themes for where we are right now on this “Rejoice” Sunday at this midpoint of Lent. We who go to church are in danger of considering ourselves to be the “saved” – the elder son in today’s Gospel story. We sometimes have the elder son’s smugness, coldness, and lack of compassion for those who are weak. The truth is that we are sometimes also like the younger son, profligately spending our inheritance of God’s grace as though there will be no tomorrow.

Some have confused God with Santa Claus. Others believe in a pussycat God who forgives anything, even when one has neither the time not the urge to apologize. Surely, the father of the Gospel story forgave even before the prodigal left home. There were no conditions on his love. But the forgiveness can’t activate until the son comes home and asks for it. Sin is not a debt to a banker but an insult to a friend. But if we have no adult personal relationship with God, a sense of that insult is not likely. Some people have no sense of violating a friendship; for them God is as easy to hoax as the phone company.

No matter where we see ourselves – as the immature younger son or as the smug elder son or somewhere in between, let us accept our heavenly Father’s offer of reconciliation. Our Father’s pronouncement is, “You’re mine, and I treasure you not for what you do but because you are.” Perhaps we have to accept the hardest penance of all – to accept being loved.

Reconciliation with God – and with one another – is especially needed in our world with its many divisions. On an immediate level, the need can show itself in family rows, neighbours not communicating because of some incident that is long forgotten, words that have caused hurt. And there can be no peace without repentance and reconciliation. Sometimes it is necessary for the one offended to reach out to the offender, whose pride gets in the way of seeking forgiveness.

Overcoming those manifestations and fulfilling the proclamation of joy in the opening word of today’s liturgy can be accomplished especially in the Sacrament of Reconciliation. In an address to the Second Vatican Council, Pope Paul VI defined a sacrament as “a really imbued with the hidden presence of God.”

To participate in the sacrament of Reconciliation is especially fitting for Lent, but its frequent use at all times has many values. Every time we go to the Sacrament of Penance, or Reconciliation, or Confession – whatever we are in the habit of calling it – we acknowledge that we have culpable sins; we affirm that through the mercy of God no sin is unforgivable; we implicitly testify that God’s mercy comes through the priest from Jesus, who forgives sins; we attest that the Church is a mother who loves us, even when we can’t love ourselves; we implicitly confirm that God wants us to reject a part of our past life, so that the days ahead can be better than those behind; we experience God reaching out to welcome sinners home to renewed relationships with community and with ourselves; and we implicitly reaffirm that we can do things with God’s grace that we might not succeed in doing on our own.

Thus cleanse, we can spread our reconciliation to our other brothers and sisters. Only in that way can we go down in the Book of Lie as people who through Baptism have entered a new life whose story may not be short, but has significance into eternity.